This fall I received an email from Liz Ainslie. Liz is a friend and an artist living in New York City. Liz informed me that she was out with another friend of mine Maanik Singh Chauhan and they spotted one of my paintings in an antique store. Maanik saw the painting first and noted my signature on the back. I guess the painting was a bargain because Maanik bought it right away.

Kip Deeds, Entering the Carousel, oil on canvas, 12″ x 12″, 2003

My friends finding this painting has been a fortuitous for several reasons: first, now I know the artwork is in good hands; second, this event has allowed me to converse with Liz and Maanik; third, now I have a great reason to highlight these wonderful artists’ work.

Liz Ainslie, The Pieces XI, oil on wood, 24″ x 18″, 2010

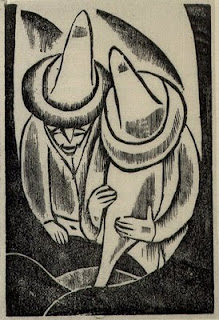

When I am absorbed by Liz’s paintings I think of a kind of abstract depiction of home through shape, form, and color. I am reminded of the playfulness of Milton Avery and the sensitivity of color that Morandi brought to his paintings. One of Maanik’s paintings, seen below, is humorous in part because of its title and also because Maanik is a Sikh. This is one of my favorite paintings; it mixes humor and seriousness in a way that causes rumination.

Maanik Singh Chauhan, Sikh and Tired, oil on panel

The chances of finding one of my paintings in a resell store and recognizing it seems slim. I feel that winning the lottery might be greater. Although the payout in this case may not be nearly as great, the power of art has once again brought people together.